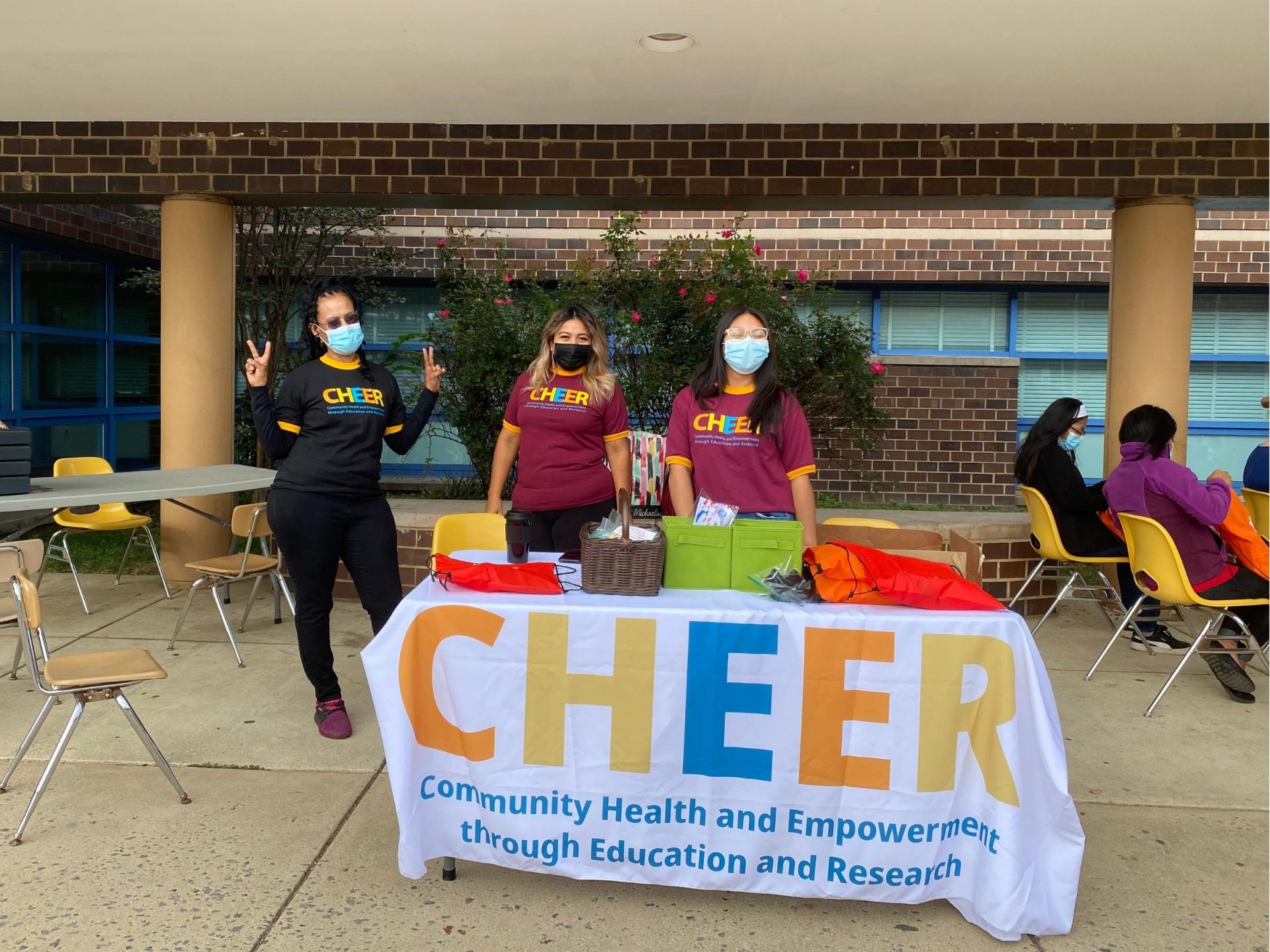

By Kelly Umaña, MPH, Community Health Programs Manager at CHEER (Community Health and Empowerment Through Education and Research).

The link between hosting vaccine clinics at an elementary school and having a great community turnout is the eminently important connection that these institutions have with community members. It was clearly demonstrated when CHEER helped organize a community vaccination event on October 25 at the local New Hampshire Estates Elementary School (NHEES) clinic.

NHEES is a Title 1 school and currently serves a large Latinx population, with 75.4% of children reported being Hispanic/Latinx. They also have a 92.4% FARMS rate, according to the 2020-2021 MCPS At A Glance Report.

It was a wonderful opportunity to confirm the value that community health workers (CHWs) bring to the table, and how valuable they are in addressing gaps in healthcare, beyond COVID-19, in the Latinx community. They are experts in the community in navigating a complex and inequitable health care system that does not serve immigrants well.

To that purpose, I want to share four stories we experienced at our event. In every single one of those, a community health worker intervention played a critical role.

#1: Promoting bilingual, Latino-friendly services

One of the families that came to the clinic had with them an adolescent boy who had been recently released as an unaccompanied minor from a detention center in Texas. It is required to receive the COVID-19 vaccine during the processing at the detention center. However, in this case, he did not receive a COVID-19 vaccine card, but a full-page letter in Spanish stating that he had received the vaccine.

The letter did not have the lot number of the vaccine that he had received, so one of CHEER’s community health workers took the time to walk through this letter with the pharmacist because the lot number is necessary to confirm that the person had received the vaccine.

After about 10 minutes of back and forth with the pharmacist, the young man was able to receive his second vaccine dose. While he was at the clinic, CHEER also connected with the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) to obtain the adolescent’s vaccine records because when we spoke with his guardian, he mentioned that they did not have this information.

This encounter demonstrated not only the critical importance of having bilingual staff but having people at the clinics who are familiar with these types of unaccompanied minors’ cases, to ensure information is appropriately communicated with the clinical partners.

#2: Walking new immigrants through the system

The CHWs also participated in street canvassing to notify the community about the clinic being held in their community. I went along as well. While I was talking with a family at the nearby apartment complex next to NHEES, they mentioned that they had arrived in Maryland only three weeks earlier and have a three-year-old daughter.

As they had not seen a primary care doctor or a pediatrician, one of CHEER’s community health workers was able to schedule an appointment to help them obtain health insurance through the Care for Kids program. When I mentioned this family to the NHEES principal, he notified me that there are some spaces left for the program they have at the school for children who are three years-old, so I passed on the family’s information so they could be enrolled in the program.

#3: Connecting people to resources

Another family who came for their first dose was one that arrived when the clinic opened at 10:00 AM. When I spoke with the person who was coming in for their first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, he mentioned that he was concerned about taking the COVID-19 vaccine because he was on high blood pressure medicine.

I was able to speak to the pharmacist to confirm that it was okay and asked the person if he had a primary care doctor. He responded no and had not seen one because he does not have health insurance. We were able to take down his information and one of our community health workers followed up with him to enroll him into Montgomery Cares, a health insurance program in Montgomery County for those not eligible for Medicaid.

These scenarios represent real events that many Latinx community members confront daily in Maryland and specifically in Montgomery County. They are afraid to take the vaccine because they do not have access to primary care, which is a broader issue that our CHWs have been able to tackle through these clinics.

#4: Following up and taking care of our community

Six of the families that came by to the clinic on October 25 were community members that had participated previously in a vaccine clinic that CHEER held together with Holy Cross Health at the Greenwood apartments. Once again, CHEER’s community health workers were able to connect the dots between events and community members by making phone calls during the NHEES clinic to families who received their first dose at other clinic sites that had been also organized by CHEER.

Photos courtesy of Kelly Umaña

We were able to mitigate so many gaps in accessing health care at this clinic by making it at a place that is familiar to communities, with a powerhouse team at NHEES that made it fun for children, and our community health workers who are continuously addressing gaps in health care services. This is what a “culturally responsive” effort looks like. This model should be replicated in so many other schools as they start thinking about the rollout plan for when 5 to 11-year-olds can get the vaccine.